by Michael Leunig

Keynote presentation delivered at 10th Dialogue Australasia Network Conference, 11 April 2015.

In a world that seems determined to go faster and faster each day; at breakneck speed for no reasons other than greed and fear, it is interesting and wise to wonder in the traditional way if our world is going mad and falling apart like never before – and that we are all caught up in this peculiar disintegration.

Nothing can be loved at speed, and I think we might be looking at the loss of love in the world due to the increased velocity of ordinary life; the loss of care, skill and attention enough to ensure the health and happiness of each other and the planet earth. It is a baffling problem and governments seem unable to recognize it, or do much about it at present.

To put it as a bleak modern metaphor, there may be moments when we feel we are all aboard an airliner being flown into a mountainside by the unstoppable forces of an incomprehensible madness. Now seems like a good time to talk about spirituality, art and innocence.

Why do I choose to put together this wonderful holy trinity of spirituality, art and innocence? Why do I feel so mystified, yet so at home and secure with these three ideas? Why the need to try and illuminate my ever deepening ideas about them, and yet enjoy watching them disappear beneath the depths of understanding or into the cloud of unknowing?

The simple truth is that I believe these things are treasures that matter hugely to the health of the individual and society - and because of man's influence on the environment, these things matter to the entire ecosystem. I will address each of the three quite separately in terms of what they mean to me, and what has become of them in the modern world. Though I may describe them separately, they are in fact connected to the point of being aspects of the same concern. They are a vital part of the ecosystem - which in earlier times was thought of as the soul - and this may well be an ecosystem under such enormous strain that it is causing the world to become deeply unwell.

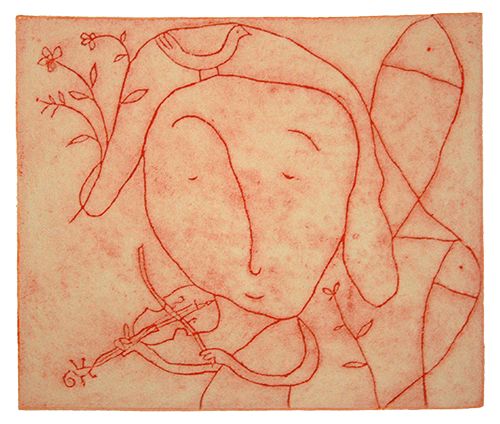

In my work as an artist in the media over the past forty-five years, the concepts of spirituality, art and innocence have gradually strengthened and played a huge part in my creative process and thinking, both consciously and unconsciously I believe.

I will begin with spirituality. To put it mildly, a vast wealth of scholarship, literature and philosophy has accumulated about the subject of spirituality, and it would be fair to say that a lot of it is hyperbole and delusion. It would be reasonable and not too cynical, I trust, to mention that there is a huge spirituality industry, including branches of organized religion – much of it amounting to nonsense, authoritarian power obsession and commercial opportunism.

It is indeed a word that is much used and abused, and therefore might be illuminated and refreshed when handled as simply, frankly and innocently as possible; it is one of those areas where each of us may feel properly entitled to have our own definition or understanding of what it’s all about.

Our spirituality is innate, idiosyncratic and natural, and it would be futile for me to try to examine the matter too closely or elaborately in this limited discussion. I am not equipped to do so anyway.

I have come to understand my spirituality as an ongoing internal lyrical state of consciousness, semi-consciousness and unconsciousness in which I find meaning, comfort, refuge, inspiration, mystery and strength.

It seems more like the dreaming of my inner child's creaturely heart than my rational mind – although they are both interwoven. It is somewhat like music. It is like nature. It offsets the influence of my worried contemporary self or the hard speedy material world that would overwhelm me if it were not for this nourishing sense of otherworldliness, and the lyrical wisdom and feeling that arises there in my spiritual self.

With spirit, one is able to have and hold many feelings, and live a felt life. The spirit supports and negotiates between our feelings, instincts and intuitions. It is good at conflict resolution. It supports our prophetic vision and our creativity. With spirit and feeling we may find a way through the darkness.

I cannot help but think that a rich and confident spiritual life is a form of genius.

Working in the media as a commentator on politics, society and the brutal stories of misfortune and human malice is indeed a gruesome and despairing task for a sensitive soul, perhaps too much for a lone individual to bear for too long. One needs support, collaboration and consolation at least. One needs epiphanies and a visit from the angels as practical necessities. This is where the spirit comes in; it is a conduit to, and from a divine world.

Often in my work and calling, it has seemed to me that there is another being within, another self – perhaps the true self – which is not beholden to this time and this world; an eternal collaborator helping me to go it alone in making sense of the chaos scattered before me. This true self is not something I rise up to, but rather a state I descend to; a regressive surrender to a deeper, more primal and enchanted place within; a more free and timeless sense through which I feel beauty amidst the unbearable ugliness; a poetic vision in which I see a measure of redemption, healing humour, or a deeper and higher picture of life and death on earth; an inspired liberating perspective which enables me sometimes to find words and symbols, or expressions that may be of value to my fellow creatures as well as to myself. I am talking about the spirit. The spirit gives momentum and ease to the soul's natural genius. The soul is a great genius.

Might I say that from a worldly perspective, many could regard this inner state as a delusion or type of madness, in which case I would call it a divine madness which has taken form as a mystical helper and healer; it is my secret garden in which valuable and wondrous things are growing, a productive cultivation that I must protect and care for.

As Zorba the Greek said, ‘a man needs a little madness, or he will never dare to cut the rope and be free.’ I have found that if one is to have and enjoy and be helped by one’s spirituality, it is necessary to at some point cut the rope. If we listen too much to the fast-moving, rational world and its ubiquitous cult of cleverness, it would perhaps quickly try to disabuse us of our spirituality, de-construct it and prove to us that it is primitive, delusional and counter-productive. Perhaps the human spirit is threatening to the established order.

The spirit lies at the heart of our character and personality; our individual, divine self, which is one of the greatest treasures we will ever have access to.

Yet the spirit is an insurgent also, and there is rebellion and defiance involved in the recognition and protection of our inner life. Often such rebelliousness is against institutions like the church, the state, the family and the culture in which we live.

The valuing of spirituality may involve pain and huge inconvenience, and it will also help reveal to us not just the beauties of creation and the miracles of life, but also the dark tragedies and the sordid aspects of human nature – or chilling visions of the future, for not only is it crucial to our innate prophetic vision, but it is also the life blood of the natural genius endowed to all of us at birth.

How else do we hear and make music, or know beauty or cry or play or grieve - except through our spirited spiritual self? How do we stay sufficiently sane in a mad world, except through our spiritual hearing and our spiritual gaze? How do we empathise and see compassionately into the suffering of humanity and self – or the suffering of the creatures and nature - except through our spirited spiritual heart? How else do we love? Spirituality is surely the breath and breathing of love in the world.

Any discussion of spirituality is bound to lead to, or include ideas about God.

I have recently written a tiny essay, as a prelude to a book, about my personal feelings concerning God and the word God. The writing of this essay was for me a re-exploration and clarification of my concept of God, and how I came to discover the word in my innocent childhood. I learned it not by instruction, but rather by osmosis and as a natural part of ordinary domestic conversation – not as a theological concept or part of any dogma, but simply a folk word that a small child absorbed and made his own sense of.

I would like to share this piece, because although it addresses the idea of God, it may well be seen as an expression of some of my ideas about spirituality in general, and in fact, the word God may, for the purposes of this discussion, be replaced by the word spirituality. So here it is.

“I use the word 'God' … conscious of the fact that there are many who may find it objectionable – and others who may find my casual use of the word too irreverent or shallow. For all sorts of reasons people can be very touchy about this word; in my view they seem either too earnest, too proprietorial, too fanatical, too averse or too phobic... There is however no ultimate authority or definition. The word is yours or mine to make of it and hold or discard it as we will.

When I first heard the term 'God' in childhood I was not sure exactly what it meant, but this was not a problem; it was simply a word inherited from the world around me and was more cultural than religious. What can a child make of this? It was a plaything for the innocent mind. It seemed related to the fairies and pixies and this was rather pleasing. I said occasional childhood prayers to God without understanding who or what this God was and enjoyed these mysterious little moments muttering to something that seemed good and somehow on my side.

My grandmother sang songs that included the word and this all seemed enjoyable and harmonious. Father would sometimes utter the phrase ‘God only knows’ or ‘God help us’ or ‘God strike me blue.’ And mother too – she used it in similar ways – it was mostly just a useful all-purpose folk word in my mother tongue. It was there floating about and I accepted it.

Later on in life at school, it became a more religious or serious theological term, yet this did not clarify things very much. I became aware of strange, awesome imagery and extravagant ideas that were put about concerning an all-powerful creator God and stories of the wonderful and terrible things that had been done in God's name. Eventually I got caught up in rational debates and questions about the existence of God and whether I believed or did not believe, yet could not quite understand all of this and did not feel too perplexed or concerned about my failure to properly grasp the meaning or have a definite view. The point is that I was always fairly at ease or indifferent about this word and held a cheerful view that it was part of an ancient, ongoing, non-threatening mystery.

Later on I noticed that certain educated friends found my ambivalence about the word and willingness to happily use it a sign that I was probably too irrational and superstitious and not modern or scientific enough. I in turn wondered why they, with their apparently resilient open minds, were so het up, so squeamish and almost phobic about it, as if it were an embarrassing obscenity – this word that had been used quite naturally, not just by many of their ancestors, but by wonderful creative and intelligent minds like Johan Sebastian Bach, Vincent Van Gogh and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

What were these extraordinary free-spirited artists referring to when they used the word? What personal inner state, what idea, what spirit or sensibility, what part of self, what other-worldly principle, what eternal beauty or truth? This became to me a rich metaphysical contemplation.

I have thought that perhaps it requires a daring creative imagination or a sublime lyrical vision to use the word meaningfully and with ease or equanimity. Perhaps it requires a very free and flexible mind or the capacity to not know and not worry too much – and yet the ability to be fully alive to life's spiritual possibilities and the capacity to have and use and simply enjoy a vivacious mystery.

Apart from the obvious appalling uses and meanings of the word in history, it also seems to have been used to reference something natural, valuable and vital; a thing so deep and wide or so beautifully light that is was practically unsayable because no word existed to describe such a state or such a thing. And so, a more free, enlightened and helpful interpretation of the word is possible – ‘God’ as a sort of shorthand or password, a fertile inconclusive everyday expression, a signpost, a catalyst, a spark, a stepping stone, a bridge, a makeshift handle ... A simple, robust word used lightly and loosely or as devoutly and deeply as we might feel – and a way to break free from this material world for a moment or two, a day or two... or for what's left of a lifetime.

And eventually for me; it is a lyrical word, a poetic word – in fact a one word poem. And finally the idea emerges from the poem that this 'God' I have been talking to and happily wondering about is indeed the god within; the god of self: true innocent self - the lost beautiful suffering joyous self. Dear God. That's more or less how I have used the word in this book.”

Any thoughts of spirituality lead me quite naturally to the idea of art because in my view, and in my experience, art is an aspect or an expression of our individual spiritual reality.

Art is a manifestation of the personal interior state and is not entirely of this world. Like the spiritual dimension, it is significantly other than this world and therefore is a great relief from all things banal, conforming and aggressively secular or profane; a cathartic healing relief which every struggling human soul requires. Perhaps it is a flight into beauty and eternity.

Many would argue strongly that art is precisely and explicitly about our material reality and our prosaic worldly circumstances, and while I would agree that this can be importantly so; it would appear to be the case that such art is becoming more of a calculated, intellectual affair.

This drift to the intellect has produced art which in many ways has paradoxically become obscure, exclusive, encoded and indecipherable, and I dare say it is characterised by qualities at odds with the innocence of the human spirit. In other words, a lot of it seems perverse, destructive, inaccessible and sickening. In many ways much modern art has become incoherent and confusing to those in most need of art’s enriching qualities, challenges and enchantments. I would also say that it has become less soulful, less prayerful, less joyful, less natural, less loving and much more neurotic than ever before; certainly a cathartic therapy for its practitioners perhaps, but much of it a confusing, chaotic influence in the living struggling culture of the people. This to me seems like a failure. In the words of historian Sir Kenneth Clarke about modern art, we must beware of energy posing as talent, and freakishness posing as originality. Much of the incoherent, dismissive and shocking quality in contemporary art seems a failure, because I think it is the artist’s natural instinct to care for the health of society and creation somewhere deep in their work, not necessarily overtly, but somewhere in the motivation for making art is the desire to nourish, to illuminate, to heal and bring joy, mystery and meaning. To express what is repressed.

I make the point that mystery is not confusion, rather it is an enchantment of the imagination and spirit. Indeed art is a spiritual project.

I suppose what I am saying is that Western art has in many ways lost its joyous quality. It has become an earnest hierarchy unto itself, in many ways exclusive and fashion or media driven; a pompous self congratulatory domain of prize-wining celebrity artists and curators, rampant commerce, baffling and convoluted art scholarship, and a cluster of cynical ambitions for power and fame – all at odds with art’s eternal, spiritual truth and sincerity.

The art world has substantially fallen victim to its own delusions and become like a high church wielding a repressive and unapproachable theology – often posing as something chic, cool, clever and hip – and massively self-important.

Yet in spite of this, in the life of the young, the alienated and the uninitiated, individuals begin to paint, people write poetry, create literature, compose music and struggle in their spirit as they have always done to give expression to some sublime emerging revelation within. As the old wellspring becomes dirty and muddy, a new spring bursts from the ground in an improbable faraway place.

In essence, spirituality and art are interwoven in their raw searching, in their expression, in their courageous unknowing, in their joy and darkness and in their radiant innocent strength which finds its way into the human heart. Through the miracle and mystery of the need to communicate, to touch and be touched, to move and be moved, art continues to flourish and feed the human spirit. The spirit of the artist seeks to reach the spirit of other – it is an eternal impulse in the nature of human kind; an ongoing spiritual cross-pollination.

The mention of a new improbable wellspring leads us to the idea of innocence. Of course innocence is not something that can be pursued, but I believe it can be recognised and valued – and thus it can survive and be of great consequence. It can be known and understood, not just as a negative quality where something is missing – some knowledge, or experience unrealised, but rather as a rich contented state of vitality, wonderment and not knowing; a pleasure in accepting mystery and the blissful freedom of openness and unsullied imagination.

This might somewhat describe the innocence of childhood moments of wonder, horror and amazement about natural phenomenon, or the incomprehensible world of adults around them; the seeing of one’s first meteor, the first witnessing of baby chickens emerging from a nest, the shock of seeing human cruelty or brutality, and the many sensations of ordinary childhood experience ¬– all miracles, yet to the child, all witnessed without the knowledge of the word miracle. This amounts to an extraordinary degree of openness and negative capability –negative capability being the capacity to live comfortably with mystery and without the answers.

One might even speculate that such powerful, raw moments in early life could be the genesis or fertilisation of the individual’s unique spiritual and creative life. Indeed, such childhood sensations might well be one of the sources of the artistic impulse; the early sensations of amazement and enchantment, yet without rational understanding: an inspiring, alive emptiness and wonder for playing about in, for creating something to add to life, or even creating life itself. Negative capability is a fertile precondition to creativity; the joyous sense of wanting to make something beautiful or delightful that has never before existed, something not previously seen or heard, something original, no matter how small or insignificant that creation might be, no matter how confronting or difficult the expression.

A direct link to the wondrous, innocent experiences of childhood might, in mature age, be called mature innocence. Mature innocence: a valuable quality all too rare in art, spirituality and civic affairs; the capacity in maturity to access in one’s spirit faithful, felt memory of the innocent epiphanies and sensations of early childhood – the ability for an adult to happily put aside all conventional wisdom or habitual mindset and regress to the openness, freedom and brightness of one’s child-heart for fresh inspiration; the ability to momentarily shed one's well-formed identity and belief system in favour of a more creaturely open state of alertness to life and the moment.

I believe in mature innocence and its reliability. I have found some of my most meaningful, useful and joyous work there. It is my studio within my studio. We might also understand mature innocence as mindfulness.

And why do these three things matter – spirituality, art and innocence? Why should they matter in a fearful, fast-moving, overheated technological age; in a cultural climate that is increasingly secular and dismissive of these immeasurable treasures; these truths which would appear to be ephemeral, irrelevant, self indulgent or pathetic to a world dominated by a political culture obsessed with money and war?

How could the concept of a child’s innocence and its consequences upon the future of the planet be taken seriously, or seen as sacred in such a hard, pragmatic and cynical culture? How could art be much more than a commercial commodity or media novelty? Why would spirituality in all its invisibility and mystery be understood as crucial to the sanity of society and the future?

Could it be that this sublime, holy trinity I have been discussing, plays a vital part in the essential business of making sense of ourselves and our world – lest we go mad and ultimately, lest the whole world goes mad? Could it be that spirituality, art and innocence are some of our most important agencies of intelligence, liberation and wisdom? Might it be that a capacity for wonder; the capacity to remain open to all manner of possibilities – the possibilities of change, reconciliation and forgiveness, the peaceful integration of our opposites, the acceptance and love of the natural world, the redeeming capacity for love, beauty, joy and humour in a world grown anxious and pessimistic – might these seemingly improbable qualities be the creative counterbalance to a lopsided world? I think so.

Michael Leunig is an Australian cartoonist, writer, painter, philosopher and poet. His commentary on political, cultural and emotional life spans more than forty years and has often explored the idea of an innocent and sacred personal world. His work appears regularly in the Melbourne Age and the Sydney Morning Herald.

Michael Leunig, When I Talk to You, HarperCollinsPublishers, 2014, pp 11-13.